Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar is an ethnologist, art historian and sociologist; she is employed as a curator of folk art and pictorial sources at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum (SEM), of which she has been the director since 2005. Her research fields are the interpretation of Slovene sources, visual culture, the museum’s history and the symbolism of national identity. She was awarded the Valvasor Prize for the exhibition Love is in the Air – Love Gifts in Traditional Slovenian Culture. She is the co-author of the permanent museum exhibition Between Nature and Culture. Her major publications are The Slovene Ethnographic Museum: A Journey through Time and Only Partly through Space, Painted Beehive Panels and Depicted Traces of National Identity.

As the director of the museum, you must have certain priority tasks. What are they?

Research and communicating our knowledge of the wealth of ethnological heritage are of key importance; on how Slovenians struggled to survive, in what way and how we realised our everyday and festive occasions, what values we nurtured and how we created the symbols of our identity. I believe that such knowledge is also important for our identity today; it is a source of confidence and the creation of excellence for the future. Therefore, our priority task will be further research, and the presentation and communication of ethnologically relevant topics in the discourse between past and present.

The 90th anniversary of the museum was celebrated this year. How did you mark these nine decades?

We decided to celebrate the anniversary actively throughout the year. The festivity was the central theme of all events. At the scientific symposium, ‘Praznovanja: med tradicijo in sodobnostjo’ (Celebrations: between tradition and modernity) with our fellow ethnologists we tried to establish what ethnology means today in the context of celebrations. We also used the Summer Museum Night to present the ‘Passages’ project, because we think that a museum is constantly being transformed or in transition, for which we joined forces with the Academy of Visual Arts Ljubljana, whose students contemplated transitions visually and devised several installations and constructions. We created a copyright film entitled ‘Time of Aliquot Parts’, which was made by video-maker Miha Vipotnik, who used our film material and new footage to create a cinematic synthesis of symbolic harmony and the life of the museum. The central event was the opening of the exhibition on doors, which was more than just a comprehensive ethnological interpretation of the ethnological content, but also symbolised the continuous opening of the SEM’s doors to the public.

What is the story behind the museum’s establishment?

The actual beginning of the ethnographic museum dates back to 1923, when Dr Niko Županič, an ethnologist and anthropologist, was appointed director. At the time, the collection included 3,502 exhibits. Soon after its establishment, Dr Stanko Vurnik, the first curator, came to the museum and introduced planned field work, research and collecting. He focused particularly on researching Slovenian houses, painted beehive panels and peča (kerchief) as part of national costumes in terms of their development, typology and history, using the methodology of art history. He died in 1932, still relatively young, but he managed to collect many artefacts for the museum collection during his active expert period. His collection was a good foundation for the museum’s development. Dr Rajko Ložar, who managed the museum during the World War II, made a particular impression on it, and as the editor, saw to the publishing of the monograph Slovensko narodopisje (Slovenian Ethnography), one of the fundamental works in Slovenian ethnological literature. After the war, he went into exile, and then moved to the United States. The management of the museum was taken over by Dr Boris Orel, who developed a system of group research in Slovenian ethnic territory. The teams included ethnologists, students, art historians, sketchers, and others. They particularly researched the folk culture of Slovenian people. Over thirty such teams were formed between the post-war period and the 1970s, and it was these teams that collected the majority of the museum’s material, with regard to artefacts and documentation. The items were also recorded and photographed, and descriptions of the items were drafted. The period of Dr Boris Orel was truly a turning point and very active in terms of the development of museum work at the SEM. Dr Boris Kuhar continued Orel’s work. His period saw numerous temporary exhibitions, which were thematic and dedicated to crafts, national costumes, architecture, etc. They also focused on professional groups, such as the wood-workers and sawyers of the Southern Pohorje and rafters on the Savinja River. At the time, these were important new subjects, which also saw the opening of the Museum of Non-European Cultures in Goričane near Medvode, which focused on non-European collections and hosted numerous exhibitions with non-European themes. So that was a very active time also in terms of promoting ethnological content and materials.

However, it is true that there was always a desire to have an independent ethnographic museum in Slovenia in one location.

That is true. We were able to do that in the 1990s. Two buildings of the former barracks on Metelkova were renovated. One is now the office building and the second serves for exhibitions. We were also able to arrange storage facilities here, which were previously located at the premises of the Ursuline Convent in Škofja Loka. We were thus able to develop a programme with two permanent exhibitions and many temporary exhibitions, public programmes for children, youth and adults, and various workshops. We publish books and periodicals and organise various projects funded from European funds. I can say that we have become a modern ethnological museum with diverse museum activities, which focuses on our mission of researching, presenting and communicating ethnological knowledge, and integrating contemporaneity with tradition in the culture and way of life of Slovenians in their homeland, spanning its borders and further abroad and their dialogue with the world.

What were the first collections?

The non-European collections were the first that initiated the collection of ethnographic material. The first was the so-called Baraga Collection of artefacts from the Ojibwa and Ottawa tribes of North America, which missionary Friderik Baraga sent to Ljubljana in the 1830s. Another important non-European collection was that of Ignacij Knoblehar; it came from Southern Sudan, where he worked as a missionary in the mid-1800s. He studied the people along the White Nile and collected material evidence about their lives. It was only towards the end of the 19th century that the collection of ethnographic material relating to Slovenians living in Carniola actually began. The first collections of the ethnographic museum began to emerge, such as the collection of painted beehive panels, a collection of national costumes and their components, embroidery, various small craft products and the like. At this point, I should also mention the efforts of archaeologist Walter Schmid at the beginning of the 20th century, since he dedicated his time to collecting ethnographic artefacts at the Provincial Museum of Carniola and also organised the presentation of collections in Vienna.

In your opinion, what is the relation between museums and the formation of Slovenian national identity in the past and today?

We know from the past that our museum predecessors tried very hard to influence the formation of Slovenian national identity. Unfortunately, they did not have such good conditions and the means that we have today. Our goal is actually the same. We wish to share our knowledge about the ethnological heritage as the reflection and expression of the national identity past and present, and pride in its richness of content and expression, with Slovenians and visitors from abroad. We also strive to establish intercultural dialogue and emphasise the wealth of cultural diversity. I think that we have an excellent museum, which serves as a means to attain these goals with every new project. We have also noticed that the crisis has caused something of a decline in the number of visitors. But we still pursue our objectives and wish to continue to attract visitors with high-quality and content-rich projects. We hope that a visit to the museum will give them a memorable experience and make them want to return.

Where did Slovenians obtain most knowledge and artefacts for ethnological collections? Which artefacts and fields of ethnography were most interesting to Slovenians in the past and which now?

Field work and study form the basis for expert and research work. If we look back at the work of our predecessors, who are still our ideals, we see that collections, knowledge about them and the theoretical bases produced by comparative studies are the results of their intensive expert efforts, which can be realised today particularly by participating in international trends and organisations and by transferring best practices to our environment. In recent decades, the need – which must also be our commitment – has been growing for knowledge about ethnological heritage that is acquired through expert work is passed on to the public. About the interest of Slovenians in ethnographic themes in the past, we could say that they were more interested in spiritual culture in the 19th century, in the form of folk songs, tales and sayings, for example; towards the end of the 19th century, their attention was drawn to material culture, particularly to its aesthetic components, as symbols of national identity: more precisely, to national costumes, decorated furniture, architecture, and painted beehive panels. In the 1930s, some people tried to integrate these components into a distinctive Slovenian national style. Certain visitors to the SEM are still interested in the ‘classical’ ethnographic heritage. However, our expert efforts are directed towards putting exhibits in context, i.e. to modern ethnological and museum approaches.

How do Slovenians who do not live in their homeland contribute to museum collections?

The project ‘Ročnadela.org’ must be mentioned here; it is an online archive organised in cooperation with Slovenian women living in Australia who helped to collect, evaluate and contextualise handicrafts important for their identity. The project’s website enables it to continue. We also cooperate with foreign collection holders and publish a special series called ‘Zbirke s te ali one strani?’ (Collections from This or the Other Side?). The catalogue of the collection of exhibits from the new Museum of Fishing in Križ near Trieste is to be published soon.

A permanent exhibition is important for every museum. You have two of them.

In 2006, we opened the first exhibition, entitled ‘Between Nature and Culture’. We wanted to showcase the wealth of our collections; until then, most of the collections were kept in storage due to the lack of exhibition premises. The material, social and spiritual culture of Slovenians relating to nature and tangible objects used every day or on special occasions were our starting points. The second permanent exhibition, ‘I, We and Others – Images of My World’, focuses on individuals and their identities. We are continuously improving it by inviting individuals to showcase their life stories relating to this exhibition. This is not a static exhibition; it lives on. In this respect, we could say that the SEM is an inclusive and participatory museum.

And other interesting exhibitions?

The most topical exhibition at the moment is ‘Doors. Spatial and Symbolic Passageways of Life’ which commemorates the 90th anniversary of the museum.

What is your cooperation with foreign museums like?

We cooperate, for example, with the Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art in Vienna and the Italian Museum of Uses and Customs of the Trentino People in San Michele all'Adige near Trento. We also cooperate with ethnographic museums in Sofia, Warsaw, Marseille, Skopje and Zagreb, with whom we have researched our common traditions of carnivals, organised a travelling exhibition and conducted joint field work. The European Roma Route project connected us with the British, Germans and Romanians in order to raise awareness on the wealth of Roma heritage in Europe. Among the projects dedicated to Roma culture, I should also mention the project, ‘I See You – You See Me’, which we organised in cooperation with the Department of Sociology of the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana and Slovenian photojournalists. Under their mentorship, the Roma children photographed people in their community and others. The exhibition of their photographs was showcased at the Council of Europe in Brussels, in the Palace of Nations in Geneva, and elsewhere. In the field of non-European collections, we particularly collaborate with the Museum of African Art in Belgrade, and on online exhibitions with museums with Asian collections. The cooperation with foreign museums is very broad, also within the framework of exhibition projects. In 2004, when opening the exhibition premises, we invited 14 ethnographic museums from 14 countries to introduce themes that they considered important to the identity of their own nations, thus making a collage of very interesting European stories.

Which of the world’s museums do you find particularly inspiring?

In terms of its concept, the new museum in Marseille is very interesting. It incorporates a broader Mediterranean aspect in its presentation and thus many historical factors, influences and ways of life in the wider Mediterranean region. Some museums with non-European collections are also very innovative. One of these is the museum in Leiden in the Netherlands, which has a very rich collection, particularly from the colonial period, and it successfully interacts with the countries of origin of its collections. A new permanent exhibition is taking shape at the World Museum in Vienna (formerly known as the Museum of Ethnology Vienna), where non-European collections will be presented from the viewpoint of the Austrians. This is the same principle that we follow in the SEM in the relation between Slovenians and other cultures. Among ethnographic museums with national collections, I do not have a favourite. If I had to choose one, it would be our SEM in Ljubljana.

Do you also cooperate with embassies?

We nurture contacts with foreign embassies in Ljubljana. These contacts are occasional and include celebrations of their national holidays, when we try to combine them with exhibitions and thematic events which display their cultures and characteristics. One such example is our cooperation with the Embassy of the Republic of Italy. A few years ago, we organised a very successful exhibition, ‘Marimekko’, in cooperation with the Embassy of the Republic of Finland. As an example of best practice, I can also mention our cooperation with the Consulate-General of Nepal, with which we share important national identity themes such as mountains, mountaineering and alpine climbing. To commemorate the anniversary of the first successful climb of Mt Everest in 1953, we are planning to organise an exhibition and hold an official ceremony in cooperation with the Museum of Gorenjska.

What are you preparing for your visitors in 2014? Any new surprises?

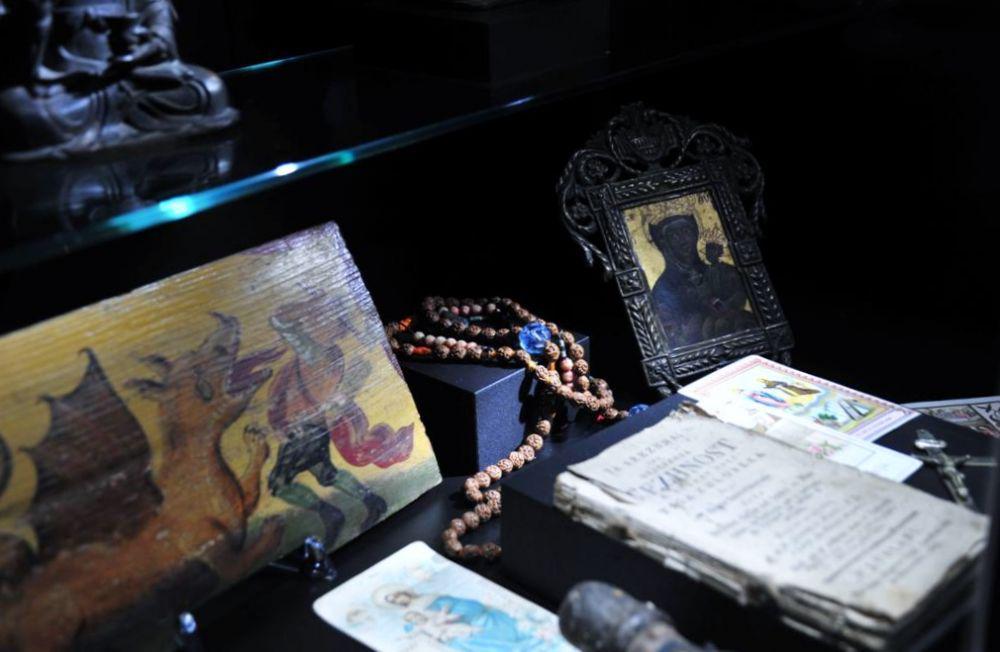

Our central exhibition will be dedicated to the magic of amulets. However, we want to continue to promote the exhibition on doors. We are planning a special exhibition to mark our cooperation with designer Mojca Turk, who has been involved in creating the visual image of the SEM for many years. We also plan an exhibition of illustrations by painter Huiqin Wang, which she is publishing in a book format; it will be dedicated to the life and work of Avguštin Hallerstein, a missionary and astronomer born in Mengeš, who worked at the Chinese imperial court in Beijing in the second half of the 18th century.

Tanja Glogovčan, SINFO

Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar is an ethnologist, art historian and sociologist; she is employed as a curator of folk art and pictorial sources at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum (SEM), of which she has been the director since 2005. Her research fields are the interpretation of Slovene sources, visual culture, the museum’s history and the symbolism of national identity. She was awarded the Valvasor Prize for the exhibition Love is in the Air – Love Gifts in Traditional Slovenian Culture. She is the co-author of the permanent museum exhibition Between Nature and Culture. Her major publications are The Slovene Ethnographic Museum: A Journey through Time and Only Partly through Space, Painted Beehive Panels and Depicted Traces of National Identity.